June 21, 2017

Naoshima: Island of Artists

There is an island for artists in Japan's inland sea: Naoshima. We paid it a visit, and recorded our first impressions.

It was night when we arrived at the island. The crossing was smooth: twenty minutes of black waters, plastic seats and muted pools of light. We saw nothing of Naoshima until the following morning. Shivering into the midnight breeze, we were blind to its beauty.

A genial obāsan took us in that evening and brought us a customary Japanese breakfast the next day of raw egg, rice and fish. It was strange, the leap from old to new found on the island. From traditional tatami mats to smooth ceramics, ancient rock against cement. That was Naoshima entirely, a very modern concept built into an age-old natural landscape.

The south of Japan is almost tropical in August. The heat renders the elderly horizontal, forcing damp flannels on their faces and groans into their mouths; we walked by open windows and found sweating bodies silently watching us pass. The glare of Naoshima made us squint, its slick concrete buildings made bright with the sunlight.

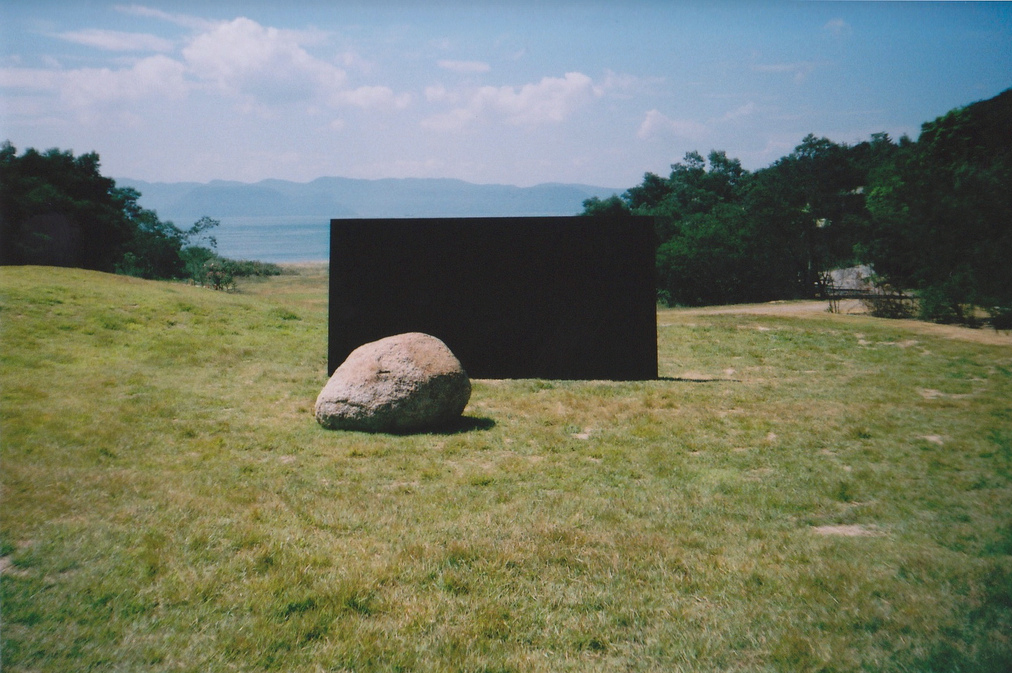

Above: Relatum, Lee Ufan, 2010

We began with the Lee Ufan Museum , designed by Osaka-born architect Tadao Ando and built in a place of relative isolation, in a valley by the sea. It is semi-underground and offered a cool respite from the blaze of the day. The minimalism of Ufan’s sculptures conspires with the smooth edges of Ando’s design to create a place of tranquillity.

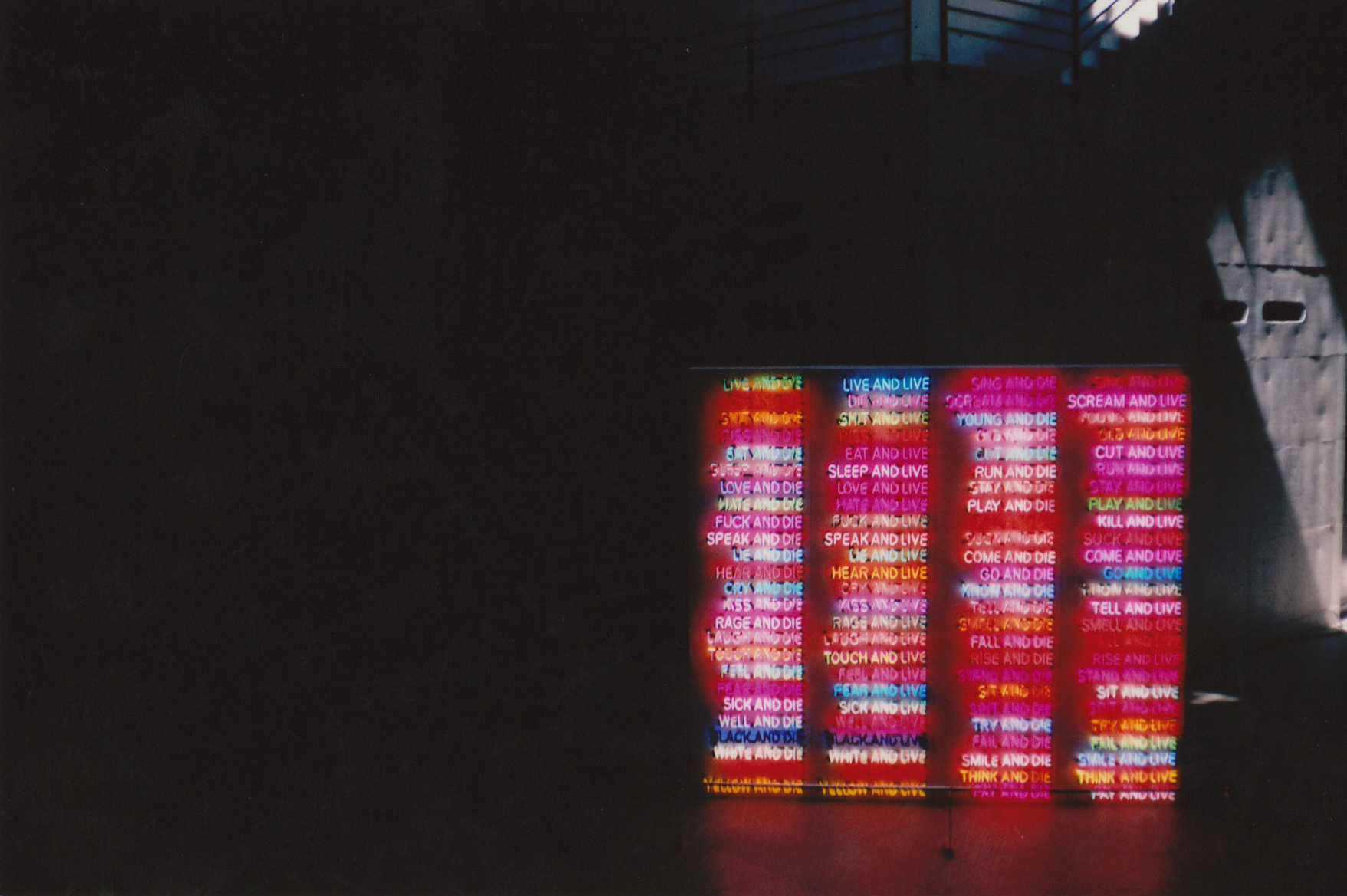

The Art House Project – in which centuries-old houses across the island are used as exhibition spaces – returned us to tradition. In an installation entitled Sea of Time ’98, Tatsuo Miyajima fills the flooded floor of a restored house (Kadoya) with multi-coloured LED lights, to mesmeric effect. James Turrell’s Backside of the Moon (found within another Ando-designed building, Minamidera) left us in the dark while an image emerged unhurriedly on the wall ahead. Elsewhere, in the Benesse House Museum , Bruce Nauman ’s neon installation One Hundred Live and Die told us variously to ‘Laugh and Live’, ‘Play and Die’, ‘Think and Live’. Among the cement and neon were familiar splashes of colour: the oils of Pollock and Hockney and the prints of Warhol. We were struck by the vitality of this art, the breathless, challenging interchange between disciplines. But – unlike much of the art and design in Japan’s metropolises – its impact revealed itself slowly, assimilated into the sleepy Naoshima mountainscape.

Above: One Hundred Live and Die, Bruce Nauman, 1984

It is an unusual site. Established by Benesse Corporation and the mayor of Naoshima in 1985, it is distinctive in its focus on the mutually valuable relationship between the artists and the island. In return for their involvement, the local community benefit from regenerative projects such as the planting of Naoshima’s rice paddies. Meanwhile, Ando’s site-specific designs complement the quiet and contemplative landscape; there is a peaceful sense of permanence to the creativity here. Elsewhere in Japan, innovation is prized over endurance. The Nakagin Capsule Tower – a relic of the short-lived Metabolism architectural movement – stands abandoned in Tokyo, ready to be razed. Shin Takamatsu's Syntax Building in Kyoto, a paean to futurism, was demolished only seventeen years after it was built. And the Ise Grand Shrine in Japan’s Mie prefecture is ceremonially knocked down and rebuilt every twenty years, a physical representation of the Shinto belief in material impermanence.

Above: The Secret of the Sky, Kan Yasuda, 1996

We left the island by boat again, Yayoi Kusama’s vividly coloured Pumpkin impressing itself on our sight long after the port had lost definition. The day remained bright and the quietness prevailed. That was the enduring feature, the thing that stuck with us throughout our visit to the island. It is the quietness that I remember now, a far remove from the pace of Tokyo, the crush of closely-populated streets, the rush hours and the bullet trains. The island demands from its visitors a stillness that is missing from much of life in modern Japan, drawing on patience for true appreciation.

I reflect on that first ferry-ride through the night and find myself reminded of Turrell’s slowly-emerging image on the wall. It felt unending, the blackness, a cold-fingered eternity on the deck of the boat and in Ando’s dimly-lit room. Yet, in both instances, it was the time spent waiting in the dark that made the beauty and brightness at the finish of it all the more remarkable.

This piece originally appeared in print in So It Goes Issue.3, Spring 2014.

Words: Xenobe Purvis

Images: Kerensa Purvis