October 06, 2012

Klein and Moriyama

Klein and Moriyama's retrospective at the Tate Modern invites an interesting comparison between the two photographers.

The current Klein/Moriyama retrospective at the Tate Modern invites an interesting comparison between the two photographers, born a decade apart. A partition divides their work, creating, the exhibition’s curator, Simon Baker, suggests, a ‘tennis net’ effect which highlights the division and correspondence between the two artists. The similarities between their work are obvious: both photograph life on the street and both deal, largely, in black and white, although Klein’s clean-cut monochrome often contrasts with Moriyama’s fifty shades of gradated grey.

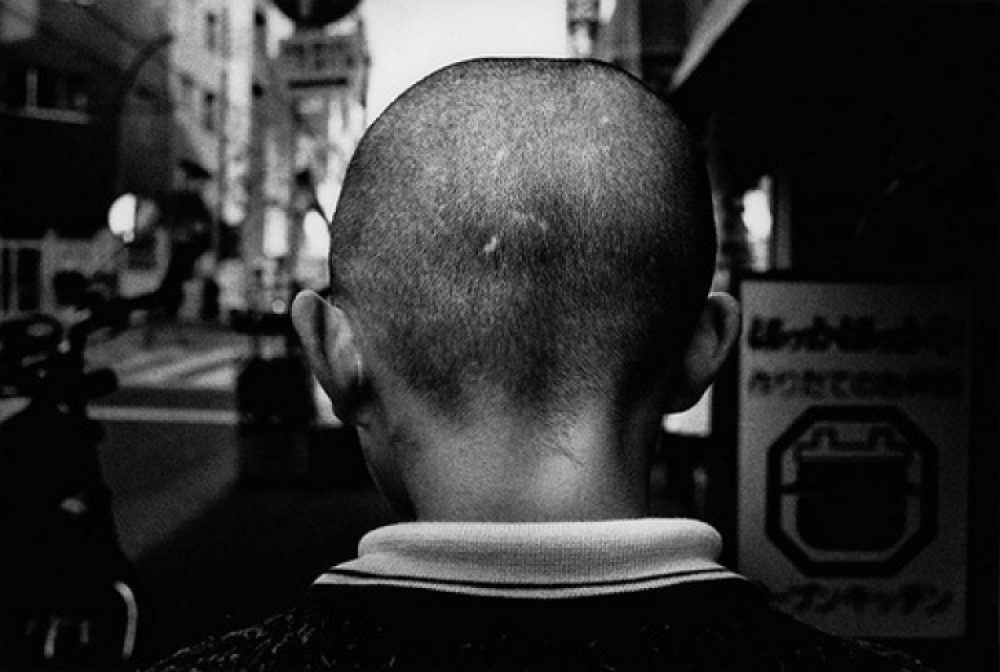

While both artists strive to create honest urban portraits, Moriyama’s work has a darker edge, a nod to the turbulence on the streets of post-war Japan. His roots in the Provoke movement of the 1960s are never relinquished, and he creates, as a result, a disturbing representation of his country, riddled with austerity. Klein’s work is underpinned with a grim sense of humour: children pointing toy guns, models strutting through the streets of Rome, misspelled street signs, and the jubilant, acrylic brush-strokes which tear across his contact sheets. Many of his photographs are imbued with a vitality and pathos which Moriyama’s stylised vision often lacks. His short film, Messiah (1999), performed by a Texan prison choir and drug addicts’ choir from New York, proves to be profoundly moving; throughout the retrospective, he delights in the charms and failings of humanity. Moriyama, by contrast, is more reserved about his fellow humans, and the effect of distance his works create leaves his viewers a little cold.